Chapter 2: Proceedings

Preparing to issue Care Proceedings

A decision by senior management within the local authority to issue care proceedings will most likely happen within a Legal Planning meeting (LPM). Within such an LPM, it is useful to discuss and agree the following once this decision is made:

-

What is the proposed care plan for the child – what is the proposed order, where is it proposed that the child will live and what are the proposals for the child’s contact/family time with their parents and key family members.

-

Timescales for completing the written evidence. This evidence is written in a specifically designed template called a Social Work Evidence Template (SWET). Some Local Authorities have a timescale of a maximum of 2 weeks to complete written evidence in order to avoid drift in issuing timescales. This timescale may be shorter depending on the urgency of the situation for the children and the necessity to enter court sooner. Please make sure that the timescale for completing the evidence is agreed at this meeting and you are clear on when you are expected to submit your draft SWET to your manager for them to quality assure it. It is also likely that the legal team will quality assure the SWET so it is important to build in enough time for this as well.

-

What is the safety planning for the child around the notice period of the hearing.

-

What other papers need to be collated in preparation for issuing e.g. previous assessments, documents from key professionals, information from previous proceedings.

What to think about when writing evidence

The social worker’s written evidence is what is presented to the court to ask a judge to decide on what should happen. The primary aim of a court statement is to advise the court on how best to keep the child/ren safe. A well written, child focused and analytical statement makes a significant impact to the reader.

The social worker’s evidence should be written in the Social Work Evidence Template (SWET). Please make sure you are writing your evidence in the most up to date SWET. The templates have prompts to help to consider what information should be including in each section: Social Work Evidence Template (SWET) – ADCS

The law is clear that when a judge makes a decision about a child in the family court, that they need to address the Welfare Checklist. This is part of the Children Act that asks us to provide information and analyse the individual needs of the child. It is important to address the welfare checklist in the statement.

Either copy and paste the welfare checklist into the SWET and address each point or cover the points when writing. It helps to know the welfare checklist well and to write from the child’s perspective. This brings the child’s lived experience as the primary focus. Highlight what life is like for the child, what is the impact on them of the parenting they are receiving, what this means for their holistic needs, and what needs to change to make life good enough for them. You can see the welfare check list here: Children Act 1989

It is important to know about the case law that shapes social work statements. ‘Case law’ is significant judgements that are published on particular cases. They examine how the law is applied to children and family situations. One main judgement often referred to in hearings is ‘re B-S’. Briefly, this is a case where the judges said that social workers and Guardians need to analyse the care options before the court, writing about the positives and challenges and what support could be provided to mitigate the challenges. There is a section in the SWET that provides for this. It is important that this is filled out per child and sibling group, looking at their individual needs. This can sometimes be the first part of the statement that a judge will read.

It’s also important to know about some other judgements, such as ‘re H-W’. Briefly, this was a case where a judge spoke about ‘proportionality’ when making an order. This is why the social worker must provide an analysis in the SWET as to what the options for orders are. This is also why the local authority has decided that the order that they are requesting is proportionate and the best option for the child compared to the other possible orders that could be made. This ensures that the court considers using the ‘least interventionist’ order and takes account of the Human Rights of all the parties to ‘family life’.

Another judgement that is referenced particularly if there is a fact finding hearing, is ‘re W’. This is the judgement that set the criteria for considering whether a child should give oral evidence in a hearing or not, and if so, how.

If the local authority is seeking interim separation / immediate removal, the social worker needs to demonstrate an imminent risk of significant harm to the child and their SWET will need to evidence meeting the separation test:

Interim separation is only to be ordered if the child’s safety demands immediate separation AND the removal of a child must be proportionate to the risk of harm to which s/he would be exposed to in the parents’ care.

It is also important to note that in an initial SWET the legal test to remove a child in the interim is that the risk of harm is ‘immediate’. In the final SWET the legal test is that the child’s long-term safety is at risk if they remain in their parent’s care.

The SWET must address all the possible care plan options for the child in the table in Section 6. Information should also be included in the Section 6 table as to why the possible care plan options have been discounted and why the local authority’s proposed care plan is realistic.

When considering interim separation, it is important to also start parallel planning for the child at the same time. In the LPM this should be discussed, along with discussions about the wider network and possible viability assessments and discussions around proposed family time between the child and key family members and relevant referrals made to appropriate teams to ensure there is no delay for the child.

Writing Care Plans

-

It is a plan for the child and how their needs will be meet during the care proceedings and beyond. Please make sure not to include evidence in the care plan.

-

Provide one care plan for each child – these should be individual to the child and speak about their individual needs and wishes and feelings.

-

Detail how the family can expect to be involved with the children, now and in the future. This will include considering, in detail, the child’s time with their parents, siblings and any other key family members (also referred to as family time or contact).

-

Include information about any proposed placement details and timescales for moving to the placement, if this is relevant to the proposed care plan for the child.

-

Always make sure that the child’s cultural practices are discussed and considered, highlighting key aspects like language spoken at home and religious practices and any specific customs or values that might impact their daily life and interactions with others, to promote a culturally sensitive approach to their care.

Top tips when writing evidence

-

Social Work Evidence Templates (SWETs) should be written in the first person i.e. I am the allocated social worker and have been since XXX. Throughout the SWET, “I visited…” or “it is my opinion that…”

-

Refer to people using their preferred title (Mrs/Mr/Ms/Dr etc) and pronouns.

-

Use the same formatting and spelling throughout e.g. for dates and names.

-

Be wary of cutting and pasting or overwriting old documents as this may lead to information about other children and families being accidentally included in court documents.

-

Social work evidence should be ‘easy to read’. Please try to hold in mind when writing that the parents need to read and understand the information in the SWET, and there is a chance that the children might read it. That means that the language used needs to be simple and jargon free. If referring to a resource or service specific to a local authority, please both name it and explain what it is e.g. a substance misuse service.

-

Keep reports/statements concise. A judge will read lots of documents and points may be lost in long documents.

-

If information is confidential, such as a refuge location, don’t include this information in the SWET. It is also important to remember to think about confidentiality and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) when writing about other people not directly involved in the proceedings in social work evidence. For example, when talking about extended family members or people in the family’s network, use their initials only or redact certain information. When providing a genogram, initials could be used for extended family/network members.

-

Always be careful about language and use descriptive, rather than emotive, language. It is important to be specific when providing evidence. Rather than ‘he has missed several appointments’, it is better to write ‘Out of a possible 15 appointments with his substance misuse worker over 6 months, he has attended 3 appointments and has not given a reason why he didn’t attend’.

-

Being balanced and fair is important. It is important to recognise protective factors and a child and family’s strengths, even if overall the conclusion is significant worry about the risk to the child.

-

Where relevant, viewpoints of experts should be included and the areas of agreement/disagreement. The reasons for a difference of opinion and conclusion should be clearly recorded and justified.

-

If expressing an opinion in respect of concern around a parenting ability, always try and provide at least two or three concrete examples of why this opinion has been formed.

-

Identify any gaps in evidence in the SWET and how this gap can be filled and if possible, timescales e.g. if there is a need for police disclosure.

-

Where there are several children and if appropriate to do so, avoid repeating information which is common and relevant to all those children. It may be more helpful to place this information at the beginning of a section and then go on to write about the issues specific to that child. This will also allow the court to concentrate on what is important for each child.

Common pitfalls

Central Family Court Cafcass Guardians shared some pitfalls that they come across when reading evidence. They have suggested possible solutions to these and where on the Social Work Evidence Template (SWET) this information should be included:

-

SWETS can be very long and detailed. It is important to remember not to repeat, if information is in other parts of the SWET it will be considered across the whole piece of evidence. Providing succinct and clear information and analysis. In Section 1, it is helpful to provide a succinct and clear overview of “which court order or order/s are being sought” and why now to provide necessary context for the rest of the evidence.

-

There can be a lack of clarity on the plan being proposed by the local authority e.g. what specific assessments are being proposed, is a placement move for the child being proposed. This information can be provided in the following sections:

-

In Section 4, there is a dedicated section/prompt about which assessments are being proposed (if any) by the local authority and asks the evidence writer to explain why these assessments are necessary. This is where to talk about where the gaps are in the information and why further assessments are needed.

-

In Section 2.3 and 5, discuss proposed family arrangements if this is applicable and detail what discussions have been had with family members about proposed family arrangements or why these aren’t possible for the child.

-

In Section 9.1, succinctly list the assessments that the local authority is proposing.

-

-

Guardians often struggle to work out where the child or young person is now (physically) based on the information provided in the SWET. Please make sure the location of the child is clearly stated in Section 2.1.

-

It is extremely important to always include the child’s recent views. Please use Section 3.3 consistently and within this section, provide a summary of the most recent piece of direct work that has been completed with the child to ascertain their views on the care plan, their understanding of the care proceedings (where applicable) and who they enjoy spending time with.

-

Don’t forget to detail all the work (including assessments, interventions and Family Group Conferences) that have taken place within the pre-proceedings/PLO process in the table in Section 4.1. In the unlikely event that no work has been completed with the family prior to care proceedings, please indicate this in the table rather than leave it completely blank.

-

If the proposed care plan for the child is immediate separation, the risk of imminent harm to the child needs to be very clearly outlined across Section 1, Section 3.2 and Section 6. Section 6 needs to clear on what placement proposals the local authority has for the child.

-

In Section 6 explicitly weigh up each legal option in the table of realistic options i.e. not just where the children are proposed to be staying but under what order.

-

In general, the Cafcass Guardians acknowledged that the adversarial nature of court proceedings can sometimes mean that local authorities feel they need to put their point across very strongly in their evidence. The Guardians wanted to highlight that it is always very helpful to have balanced reports which properly reflect not only the parents/carers’ strengths and the protective factors, but also to express nuance and professional curiosity too.

Here is where you can find more guidance to help you completing social work evidence:

Care planning for children in proceedings: Frontline Briefing (2022) | Research in Practice

Social work chronology tips

A well-produced chronology includes the sequence of significant events in a child's life. The chronology should collate all the evidence from the social work team, partner agencies / professional network, multi-disciplinary teams, or other experts and professionals.

The Significant Life Events (SLE) incorporates the chronology and adopts a more analytical style by including an analysis of the significance of the event. If you are unable to explain the significance of the event, you may be including unnecessary detail.

Chronology best practice points

-

The chronology should focus on the last two years unless an event before that point in time has a current — and therefore lasting — significance. Historic evidence should be summarised and discussed thematically within date ranges unless there is an incident of particular importance.

-

The column titled ‘Significance' is a means to add context and begin the analytical process and helps to identify themes of risk and behaviour. If you cannot say why it is significant it may be unnecessary detail and perhaps shouldn't be in the chronology.

-

The chronology should aim to be no more than 4-5 pages long, even for families with long histories.

-

A chronology should not repeat the narrative contained in case recordings, this evidence should be analysed and presented in a succinct summary.

-

The evidence in the chronology should not be reproduced in the body of the assessment, however, can be cross referenced or further analysis provided.

-

For cases of chronic neglect and emotional harm, a thematic approach to discuss patterns of behaviour observed within date periods may be helpful.

-

Avoid information overload. Reflect on what is evidence that goes towards threshold, what is there to add context, and what does not need to be included at all. Sometimes rewording a paragraph can reduce unnecessary information and focus on the evidence.

Significant Events

A 'significant event’ is an incident, event or issue that impacts on the child's welfare and/or safety. The types of incidents, events, or issues that should be included in a chronology might include:

-

Incidents, such as domestic violence, bullying, physical chastisement, injury, neglect (such as left alone, or unkempt appearance, stealing or hoarding food), police investigations, child protection investigations, substantiated and unsubstantiated referrals/allegations of incidents, incidents that indicate concern about a child's social, emotional or behavioural development, or any other incident where the child has suffered, or is likely to suffer significant harm.

-

Information about the child's health, significant medical assessments (not routine GP appointments) or diagnoses, and reports on educational attendance and attainment.

-

Parental history including care history, mental health and psychological history, criminal history, substance misuse, history of relapse, relationship history, or other history relevant to the safety and well-being of the child.

-

Stress factors, such as unemployment, bereavement, imprisonment, accidents, illness, death of a significant person, relationships and isolation.

-

Change in circumstances or relationships, such as moving home or schools, change of carer, social worker, teacher, or other supportive person or professional, immigration, or change in makeup of the home or family network.

-

Support and services offered to children and their family, including the scope of the work, their engagement, and the outcome.

-

Assessment information, including significant medical assessment/diagnosis, and expert assessments.

-

Children's Services history, including dates of intervention, outcomes of intervention, dates and category of Child Protection Plans, patterns of behaviour such as poor engagement over periods of time, significant announced or unannounced home visits.

Here is some more detailed guidance on how to write a chronology: Completing social work chronologies: Practice Tool (2022) | Research in Practice

What happens in Care Proceedings

When the local authority issues care proceedings it is asking a judge to make a decision about who a child should live with until they turn 18 and how they should spend time with people in their family. Local authorities issue proceedings as a last resort when all attempts to help the parents look after their children to a good enough level have not worked.

Care Proceedings should take up to 26 weeks. This timeframe exists in recognition of how stressful children and families find this process. Children, if they are aware of what is happening, know that a judge is going to decide about whether they can or can’t live with their family. Managing the anxiety around this, along with the impact of any neglect or abuse they may have experienced, is very hard.

Example of timetable for Care Proceedings within 26 weeks:

What is a Child’s Guardian?

In care proceedings, the child is a formal ‘party’ to the proceedings (a person who responds to the local authority’s application). The child, like the parents, gets automatic legal aid for a solicitor to represent them. Because they are children, they are seen as a vulnerable party and automatically have a litigation friend to speak on their behalf, and who will give instructions to their solicitor. This is the Child’s Guardian. They are social workers who work for Cafcass (Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service). Information about what they do can be found here: www.cafcass.gov.uk

The Guardian will visit and meet with the child. They are appointed to provide an expert view to the court in proceedings. Once care proceedings end, their work ends. How and when they undertake their enquiries during the proceedings is for them to decide. The remit of their work is set out in the Children Act, much like how the work of a local authority is set out in the same act.

It’s always important to have a good working relationship with the Guardian and to speak with them before any hearing to update them and hear their views. It is also important to let them know any significant things that are happening for the child during proceedings. Guardians should be invited to Looked After Child (LAC) reviews and other meetings.

The hearings

There will be requirements of the allocated social worker to complete various tasks ahead of each hearing to make sure it is effective. A suggested checklist for each hearing can be found here.

The Case Management Hearing

The Case Management Hearing (CMH) is where the care proceedings is for the proceedings to conclude in 26 weeks or less for the child. Good preparation for the CMH should mean that the care proceedings run effectively to the next hearing, the Issues Resolution Hearing. Good preparation also reduces the number of further case management hearings which can cause delay for the child. At the CMH any evidential gaps are identified, and necessary assessments are agreed upon to ensure that the gaps are addressed. Parallel planning for the child should also be considered in CMH directions and timetabling.

To prepare for a CMH:

-

Make sure that all relevant in-house assessment proposals are ready and shared ahead of the CMH.

-

If the local authority is proposing any expert assessments, a proposed expert and agreed draft Letter of Instruction (LOI) should have been agreed with the local authority’s legal team ahead of the CMH.

-

Viability assessments should have already been completed with extended family/network and the relevant referrals made to kinship assessment teams. The allocated social worker should be aware of the dates/timescales for any assessments being completed with extended network members.

-

The allocated social worker should speak to the Guardian ahead of the CMH.

-

The social work team should speak to their legal team ahead of the advocates meeting. The advocates meeting will take place at least one day before the CMH.

-

The social work team should make sure that they have put all the right support in place for the parents during the care proceedings, if it was not in place already e.g. parenting worker, substance misuse worker.

Between hearings, it is important that the social work team keeps their legal team updated and the Guardian is also informed of any changes. It is important to read all assessments thoroughly soon after they are filed. If there are any concerns about the quality of the assessments, this should be discussed with management and the social work team’s legal team immediately so as not to cause delay for the child.

The Issues Resolution Hearing

As it says in the name – the purpose of the Issues Resolution Hearing (IRH) is to resolve any issues that arise so that either the IRH can become an early Final Hearing or to make sure that the final hearing can be effective and take place without delay. If a Final Hearing is taking place, the IRH will also be used to set the rest of the case up to proceed to final hearing effectively.

Between the CMH and the IRH, it is important to monitor the progress of the assessments to ensure they are on track for filing on time. Ongoing communication between the allocated social worker, their legal team, the parents, the Guardian and the child’s IRO or CP chair about progress and concerns is also important. The allocated social worker should also monitor how family time, if it is happening, is going and observe this regularly to inform their own assessment and decision making around final care planning for the child.

It is always positive if proceedings can be ended by agreement with the family. Sometimes parents can take a very brave step and realise they are not able to care for their children and can sometimes support alternative care arrangements for them. Being able to support a parent through this process is helpful for them and their children. It can also help them to maintain a positive relationship after the proceedings.

If proceedings can be ended by agreement, all efforts should be made to do that at the IRH. It may be that everyone is agreed about who should look after the child, but the question of how often the child should see a family member is not agreed. That issue should be dealt with at the IRH so that the case can conclude without the need for a final hearing. A final hearing should only take place and be used if any disagreement about the plan for the child cannot be resolved at the IRH.

Please click here for information on final hearings.

The Issues Resolution Hearing

Sometimes there can be complexities to the care proceedings which mean different hearings are needed. For example, if a child has made an allegation of abuse and the parents or another significant family member is arrested and charged, there can be criminal proceedings happening at the same time as the family proceedings. In these situations, additional hearings may be needed to see how evidence in the criminal trial is shared in the family proceedings and vice versa. Sometimes hearings with the police and Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) attending the family court are also needed to help make these decisions about what can be disclosed during their investigation or what can’t be.

These situations can sometimes make the case last longer than 26 weeks and sometimes might mean fact-finding hearing is needed.

A fact finding hearing happens when there is an allegation that another person denies, and a judge needs to decide if that allegation happened or not.

These are usually about ‘threshold’ issues, relating to allegations of abuse or neglect. ‘Threshold’ is a legal test the judge needs to decide has been met for them to make a public law order and intervene in family life (and override the Human Rights of the parent to safeguard a child). In care proceedings, the local authority’s legal team write the threshold document based on the social work statements, and these are the reasons that the local authority has issued care proceedings.

If one person is saying the allegation is not true, then the judge is asked by the parties to decide what happened. A ‘fact finding’ hearing then takes place to determine the legal facts of the case, and once those are determined, a welfare analysis flows from the established facts.

Most commonly ‘fact finding’ hearings take place at the same time as the final hearing. Sometimes, if the situation is more complex or it’s a ‘single issue’ case, it may be that there is a separate fact finding hearing and that the welfare analysis, or any additional assessments, are timetabled following the outcome of this hearing. A ‘single issue’ case is a case where all the child protection issues rest on whether this allegation happened or not. One example of a ‘single issue’ case is where there has been a serious injury to a child that may be inflicted (or not), and where all other aspects of the child’s care is good enough. If the injury was found not to be inflicted by anyone and was an unavoidable accident, then there would be no legal basis for the court to intervene in the family and the case would be dismissed. If the injury was found to be inflicted or caused in the context of a lack of supervision, i.e. the parents could have prevented the injury, then there would be a legal basis for the court to intervene and the case would continue.

In fact finding hearings, the local authority needs to prove the fact. The ‘burden of proof’ falls on the local authority. It is not for the party who the allegation is made against to prove their innocence. Therefore, the local authority needs primary evidence to support the allegation(s). Primary evidence comes from things like medical reports or witness accounts from children or adults who saw or experienced the allegation. Sometimes you might need additional assessments, like a paediatrician or forensic expert to look at medical reports and photos to give opinions about what might have caused an injury and the timing of when it occurred. All these people might then give oral evidence in the fact-finding hearing. The judge will then make a decision, and that decision is the basis on which the local authority provide our further intervention and plans. Unless the allocated social worker is a witness to any issue, they would not be asked to give evidence at this hearing.

It’s important to know the difference between fact finding in the family court and criminal trials. In a criminal trial, the ‘burden of proof’ is that the allegation is proved ‘beyond all reasonable doubt’ which is a very high legal test. In the family court, the legal test is lower, and it is based on ‘a balance of probabilities’. This means that sometimes a person may be acquitted in the criminal court but found to have caused the harm in the family court. This is also the reason why a fact finding hearing might still be needed in the family court even if a criminal trial says the person is not guilty.

What other hearings might there be?

Sometimes the court might list other hearings, such as:

A Directions Hearing: this is an additional hearing where the judge will want to make further case management decisions or look at the progress of the case and re-timetable.

Non-Compliance Hearing: this is a hearing where the local authority or another party highlights to the court that the timetable and directions haven’t been complied with, and the judge re-timetables the case.

A Pre-Trial Review: this is a hearing where the judge wants to ensure that everything is ready for a final hearing or fact finding hearing. They will want to know things such as:

-

Who the witnesses are.

-

That everyone is ready for the hearing.

-

That all the evidence has been filed.

-

That any further areas of agreement can be reached.

A Ground Rules Hearing: This is a hearing ahead of a final hearing or fact finding hearing to consider the needs of a vulnerable party (adult or child) and how those will be met in the upcoming hearing. For example, if a child or vulnerable adult is giving evidence in a fact finding hearing or final hearing, a hearing like this may be needed to agree how that would happen and what additional support they need from the court and the legal representatives to ensure they are able to participate fully, safely and fairly in the hearing.

What does it mean to ‘give oral evidence’?

When the judge decides that they need to hear from people to make a decision, mostly in a fact finding or final hearing, those people are ‘witnesses’ and go into the witness box, swear to tell the truth, and are asked questions by the parties.

If you are the allocated social worker or have completed an assessment on the family, and someone disagrees with what you are saying, then you may be called as a witness.

The allocated social worker would usually give oral evidence at a contested final hearing. It’s very unlikely it would happen at any other time. As it happens in a final hearing, you will know well in advance that you, as the allocated social worker, are giving evidence and that should give you a lot of time to prepare.

What is an intermediary?

An intermediary is a professional who can support people in court to help explain the process and what is happening in a hearing. They can also support a person when they give evidence, and they can give advice to the judge about how to phrase questions to the person and how to help the person give their best evidence.

There would need to be an application to the court for an intermediary to be appointed to help that person. This would be done by the person’s solicitor. The people who can apply for this are children if they were to give oral evidence, and an adult who is deemed vulnerable perhaps because they have learning needs. A reminder that an intermediary is different to an advocate. An intermediary will only work in the court and an advocate is someone who supports people in various settings.

Here are links to relevant legislation, statutory guidance and guidance:

Adoption and Children Act 2002

Children and Families Act 2014

Children and Social Work Act 2017

Government research briefing, An Overview of child protection legislation in England:

HM Government, Working together to safeguard children: A guide to inter-agency working to help, protect and promote the welfare of children, December 2023:

Working together to safeguard children 2023: statutory guidance

DfE, Children Act 1989: Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations volume 2: care planning, placement and case review, July 2021:

The Children Act 1989 guidance and regulations

Microsoft Word - March 2021, report (final).docx

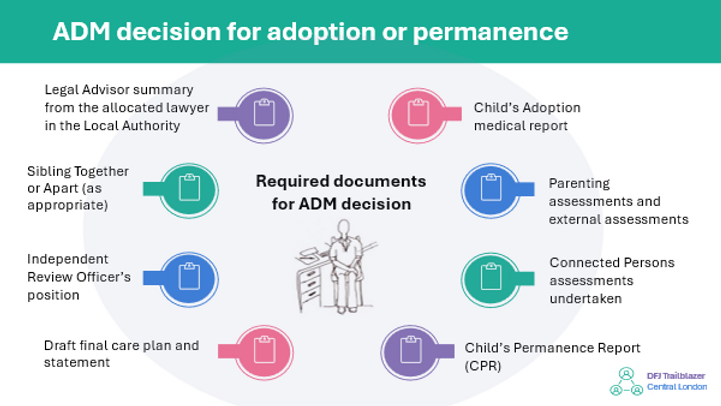

What to consider when preparing for an Agency Decision Maker Decision (for adoption):

This chapter is based on work completed by colleagues in Camden Children’s Services, Kensington and Chelsea Children’s Services and Cafcass.